What leader(s) over your product career truly changed how you approach product management?

I learned from bosses & peers, including some famous peeps like Reed Hastings, Patty McCord, and Dan Rosensweig. But mainly I learned by doing, supercharged by feedback from many "Friends of Gib."

Given the rapid change in product management roles and technologies, most of my learning has come from bosses and peers.

To answer this question, I created a list of learning from my thirty-year career. The list reinforces how product leaders can accelerate both their learning and career growth:

Seek high-growth companies. These companies attract talent from whom you learn, plus provide the opportunity for fast-paced, battlefront promotions.

Build your network of peers and mentors. These individuals provide targeted learning opportunities. You can’t get the same degree of insight via reading or courses.

Be ready to learn and unlearn. One decade, I discovered waterfall development. The next, I embraced agile.

Working with humans is hard! Learning to work effectively with engineers, designers, data scientists, project managers, researchers, marketers, customer success peeps, and CEOs is half the challenge of a product leader career.

Below, I catalog my learning over thirty years. I hope some of these nuggets will help you to avoid some of the mistakes I made.

1991: Electronic Arts (an entertainment SW company)

Trip Hawkins, the CEO and Founder of EA, interviewed me for my first product management role. Trip did a “day in the life” interview, asking me to role-play various scenarios. At the end of the interview, he evaluated me against EA’s six values. That’s when I learned how important it is to define and assess culture fit at high-growth companies.

Early at EA, Hal Jordy, an experienced game producer, helped me with two things:

How to ship a product on time. Hal’s insight: It's too hard to predict the balancing act of time, quality, and money, so develop multiple products in parallel so you can swap in one product for another. Hal helped me to move from sequential to parallel development.

How to deal with imposter syndrome. Hal was with me one day when Stewart Bonn, the VP of Product, asked me a question. I got tongue-tied. Hal's coaching: "Answer the question, Gib. And if you don't have an answer, ask questions until you can form an opinion.”

Electronic Arts also hosted a Producer College, which taught me the basic product and leadership skills required of product managers. Later, I learned how to teach these skills. For me, teaching has been one of the most effective tactics for learning new skills. Nothing forces an understanding of a topic more than having to teach it.

In my first six months at EA, I pissed off a few folks as I gave abrupt feedback. My manager, Diane Flynn, sent me to “charm school.” There, I learned how to spend more time listening and giving balanced feedback:

Here’s what you did well

Here’s what you could have done better.

My mistake when I first started at EA? I led with the critical feedback first. Oops.

1994: Creative Wonders (an educational software startup)

Greg Bestick was the CEO of my first startup, Creative Wonders. He was my boss's boss, but later I worked for him when I became VP of Product. I learned three highly impactful things from him:

Greg forced me out of the building to connect with peers. He felt this was the fastest way for me to learn. Over the years, I refined this concept to build a “Personal Board of Directors” composed of peers and mentors.

Greg helped me to transition into a formal leader. I shipped lots of successful software and embodied Creative Wonders’ culture, but the exec team didn’t trust me. Why not? I was an iconoclast — I wore shorts and flip-flops to work and had little respect for authority. Greg told me to dress better and to go to lunch with each member of the exec team so they could get to know me as a person. Two months later, I became VP of Product. The lesson: leadership is symbolic and subtle cues like what you wear matter.

Louis Roitlblat was my marketing partner at Creative Wonders. He taught me:

How to think about brand and positioning, and how marketing and product organizations can work together effectively. You can read my “Branding for Builders” essay to learn more.

How to form successful work relationships. Louis noticed I became impatient when starting new relationships. I didn’t take the time to build trust. He pointed out that I skipped the first of four steps in building a relationship:

1) Form (get to know each other to build trust)

2) Storm (Begin to challenge each other’s ideas)

3) Norm (develop shared ideas and approaches)

4) Perform (based on shared ideas and process)

I learned to be patient in the “forming” stage to let folks get to know me before I challenged their thinking in the second “storming” phase. It took me decades to get reasonably good at this. I still screw up occasionally.

Last, Tim Jenkins, our VP of Finance, helped me understand the children’s software business's reality. We broke down the COGS model, distribution costs, marketing fees, development fees, royalties to brand holders (Sesame Street, Schoolhouse Rock, Madeline, etc.). It became clear that the challenge was to deliver as much value as possible within a $300,000 product development budget. In 1995, most of the children’s software development community consequently referred to me as “$300,000 Biddle,” which, even at the time, was an absurdly low budget.

Upon reflection, my time at Creative Wonders as VP of Product taught me that my job was no longer solely focused on building products. It now required that I partner effectively with my marketing, finance, and sales peers. Before I was promoted, I would say stupid stuff like, “I don’t know what the hell finance is thinking when they propose these low-ball budgets!” But as I transitioned into a VP role, I realized how critical it was for me to build strong cross-functional alignment. At that point, I finally stopped “shit-stirring” across the different functions.

The Learning Company 1997 (Reader Rabbit, Oregon Trail)

The Learning Company bought Creative Wonders. Six months after the acquisition, I received a battlefront promotion to SVP of Product for TLC. (“Battlefront promotion” defined: When your boss leaves and you’re the last man/woman standing and the company makes a bet on you to fill the role quickly.)

My leadership learning accelerated. One of my first lessons was the extent to which a leader’s words carry. One evening I walked into a product manager’s cube to ask what he was working on. He threw a jacket over his Apple computer in an attempt to hide it. I asked him, “Why did you do that?”

He answered, “I heard you hated Macs and wanted to get rid of them.”

I laughed, then remembered the Quarterly Product Strategy Meeting where I had said, “I hate Macs.”

The reason? At the time, about 95% of our revenues came from Windows, and only 5% came from the Mac. But lots of time and resources were required to port the Mac software, which inevitably held up the Windows launch given they were hybrid CD-ROMs. But I didn’t want to get rid of all the Macs in the building! After that, I chose my words more carefully.

My biggest lesson from The Learning Company: the importance of building hard to copy advantage. We had created lots of children’s software, grew through acquisition, then sold the company to Mattel for $4B. But two years later, Mattel divested The Learning Company and took a $3.6B write-down, making the acquisition one of the worst in history. TLC had built a large category of children’s educational software, but competitors copied our work, and the children’s software category became a commodity. Today, I emphasize building a hard-to-copy advantage through brand, unique technologies, network effects, and economies of scale.

1999: FamilyWonder, a family-focused e-commerce company

After two years at this startup, Jonathan Kaplan, the CEO, took me aside to explain:

“Gib, we are going to visit Sega of Japan for a week— they want to buy us. For the first five days, we won’t talk about business. We’ll eat, drink, and do Karaoki. On the last two days, when we finally talk business, I need you to be comfortable with long silences — listen carefully. Don’t feel compelled to jump in.”

Jonathan knew some of my patterns and coached me appropriately. He also anticipated some of the challenges I would have navigating cultural differences in Japan.

That week in Japan, I took copious notes to force myself to listen and avoid talking too much. At the end of the week, we closed the deal.

2003: Epoch Innovations, a dyslexia technology startup

Keith Rabois was a C.O.O at Epoch Innovations. He had just left Paypal after its $1.5B acquisition by eBay. When he looked at the design for our new website, he told me, “I don’t care what the website looks like. I want to see the data.” Keith was the catalyst for my growing focus on quantitative data to understand how customers behave v. what they say in usability or focus groups.

2005: Netflix

When I interviewed at Netflix for the VP Product role, Reed Hastings, the CEO, asked me two questions:

“Can you delight customers?”

“Can you do consumer science?”

I answered “Yes” to both, but I learned a lot about applying the scientific method to product development at Netflix. I also learned how to delight customers while building long-term advantages. Here’s some of my key learning, largely from Reed:

Delight customers in hard-to-copy, margin-enhancing ways. I learned this mantra from Reed, and it forms the basis of my product strategy frameworks. (Here’s my “How to Define Your Product Strategy” series on Medium.)

The power of simplicity. One year, Reed encouraged me to focus on simplifying our product. While most product leaders like to build and add, we focused on simplifying the experience. This focus helped us to build a product that 200 million worldwide members can easily embrace today.

The balancing act of qualitative and quantitative. In my first year at Netflix, Reed and I debated the merit of qualitative (focus groups, usability) v. AB testing. After a year, we reached a truce where I continued to use qualitative as a source for new ideas and understand the “why” of customer behavior. But I relied on AB test results to decide whether to launch a new feature or not.

The downside of management. Reed described me as “the best manager in the building.” But he said it in an obviously critical way. His point: too much management squeezes the life out of innovation. I learned instead to provide discipline through strategy and consumer science.

I learned how culture helps talented individuals make great decisions about people, products, and business. For me, culture became an influential “anti-process.” Talented individuals don’t like rules or processes. The Netflix culture — its articulation of the values, skills, and behaviors desired for all employees — enabled individuals to make great decisions without even talking to one another.

Leslie Kilgore ran Marketing at Netflix. Reed was “all in” on AB testing. Leslie helped me form the customer's voice in my head through qualitative. Her coaching:

Get outside Silicon Valley. We moved beyond “Silicon Valley Freaks” to find “normal” customers in Providence, Memphis, and Denver, among other cities.

Get to the “why” through qualitative. Leslie often had a live video feed of focus groups playing in her cube. In a building full of “quant jocks,” it was helpful to get insight into the “why” of customer behavior by listening to our members in focus groups and usability. Leslie was an effective counter-voice to Reed.

Test big changes. We did lots of testing of our non-member site— our site’s front door. One day Leslie looked down at a print-out of six versions going into the next AB test. In looking at the postage-stamp-sized designs, she struggled to see the differences. She remarked, “If we can’t see the deltas in each version, our customers will never notice them. Our members are way too busy to detect nuance.”

The dance between marketing and product. Sometimes we’d test a hypothesis for a new feature on the non-member homepage to see if it improved conversion, and if it did, we’d build the feature. In other cases, the product evolved, and we’d bring attention to a new feature on the non-member homepage later. This “Tango” between product and marketing continued forever.

The last person at Netflix who fundamentally influenced my thinking is Patty McCord, the Chief People Officer. She helped me to solve many “people problems” in a highly leveraged way. Her advice:

When presented with a problem from an employee, ask the following question: “When you talked to this person about the issue, what did he or she say.”

In 80% of the cases, the person would go back, talk to the other person, and solve the problem independently. This tactic also helped Netflix to build a culture of “well-formed adults.”

Patty also interviewed me at Netflix. She asked me to playback some of my key learnings in my career, and I repeated a long list of stories much like this essay. She taught me to focus on product leaders’ ability to adapt and learn as you evaluate their potential for success. Learning by doing, plus seeking out a network of peers and mentors, is critical in fast-changing industries like ours.

At Netflix, I quickly embraced the two-week push cycle. I “unlearned” waterfall development and learned to build new products and features in an agile way. I found it an easy transition, likely because of our design, engineering, and data partners' talent level, as well as Netflix’s well-developed tools and systems. This is one of the many examples of learning and unlearning that I navigated over three decades. (Barry O’Reilly wrote a book, Unlearn, that focuses on this phenomenon.)

2010: Chegg, a textbook rental & homework help company

Dan Rosensweig was the CEO at Chegg. He helped me to:

Fully commit to "What's Next?" Chegg was a textbook rental company, but Dan wanted us to be much more. We eventually bought six startups to invent a high-margin digital business. The result: Chegg Study, a monthly homework help subscription service. My focus on “What’s Next?” is at the heart of my “GLEE” model for forming a product vision. (Read more here.)

Ignore the purchase price when evaluating acquisitions. In debating investments, my job was to say "Yes" or "No.” Dan trained me not to worry about the price, which doesn’t matter in the long-term. Plus, I had no expertise in startup valuation. (Dan’s insight came from his experience as COO at Yahoo! when the board passed on a potential Facebook acquisition because $1B was “way too expensive.” Ha!)

Use this deceivingly simple model to evaluate projects:

Is it big enough to matter? (This question forces you to think big.)

What does success look like? (Be clear about your vision.)

How do you measure success? (Have clear metrics to establish criteria for ongoing investment.)

As I write this, I recognize that my pattern of changing companies every five years exposed me to a diversity of thinking and experience, which accelerated my learning, too.

Conclusions

As you think back on your career, what is your most impactful learning? How did you learn? If you’re like me, you learned via on-the-job training supercharged by insight from bosses, peers, and mentors. These individuals know you, help you address your blind spots, and provide one-on-one learning opportunities.

So, how do you maximize career growth?

Seek high-growth companies that put you in proximity with talented leaders you can learn from, plus set you up for battlefront promotions.

Build your network of mentors and peers.

Be ready to learn and unlearn as both technology and your job evolve.

I hope you found this answer helpful. If you’d like this “Ask Gib” newsletter delivered to your inbox, click the button below:

Thanks,

Gib

PS. Click here to give feedback on this essay. (It only takes one minute.)

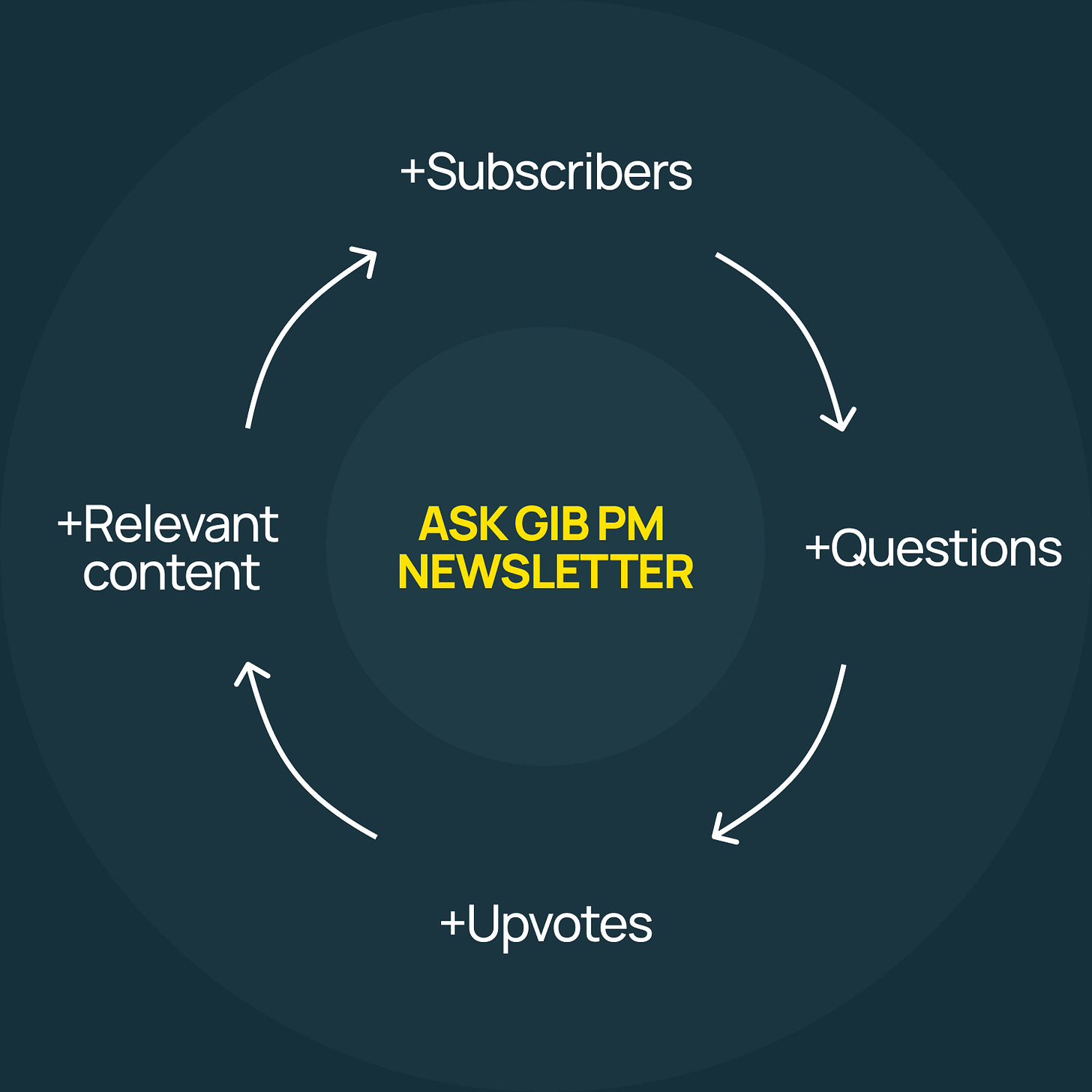

PPS. With this “Ask Gib” newsletter, I’m working to jumpstart a virtuous cycle where more subscribers lead to better, more relevant content:

So please share this newsletter with others — thanks in advance!

PPPS. Click the button below to ask and upvote questions:

Thank you!

Wonderful article, Gib!